Is understanding the Cost of Fraud the key to making good decisions?

The starting point for many improvement strategies in fraud is to simply detect and prevent more fraud, but this doesn’t always have the expected results. The metrics say your change was a success as the new rule stops twice as much fraud as the old one, so why are the fraud losses still high? Sometimes the fraud losses go down as well as the preventions going up, but the call centre is being swamped with calls. Without a full view of the fraud ecosystem and what is termed the Total Cost of Fraud, you could be making a less than optimal decision because you don’t have all the facts. In this article, I will look to cover some of the basics as well as the complexities of calculating the Total Cost of Fraud you may encounter.

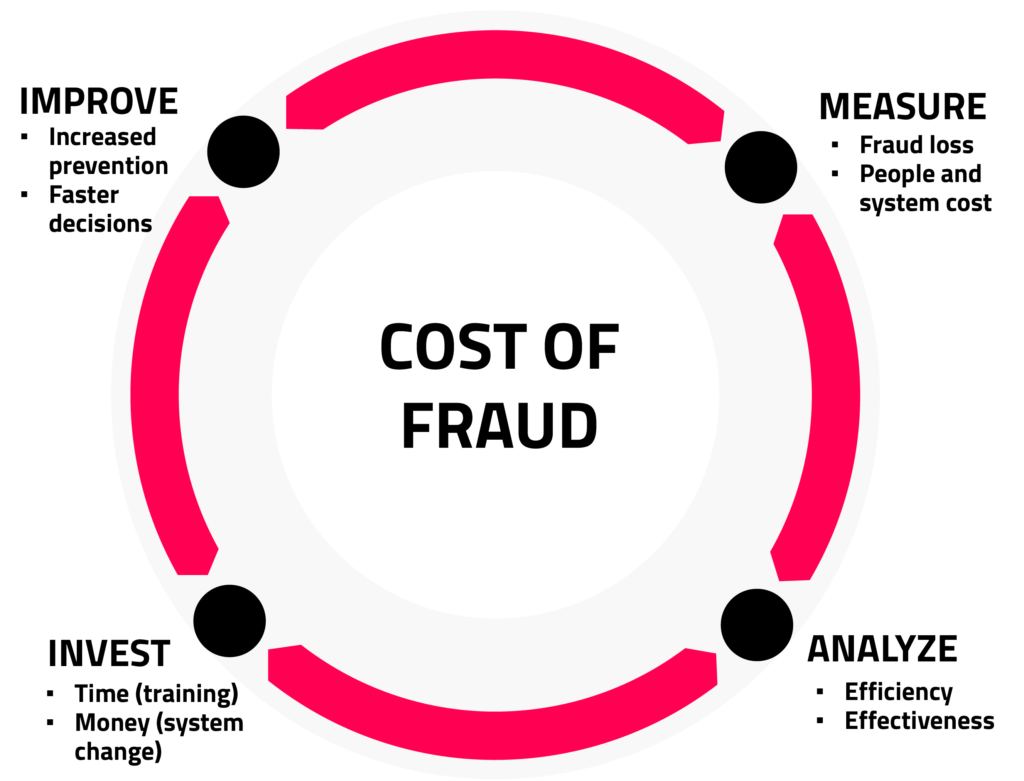

Measuring and Improving the Total Cost of Fraud

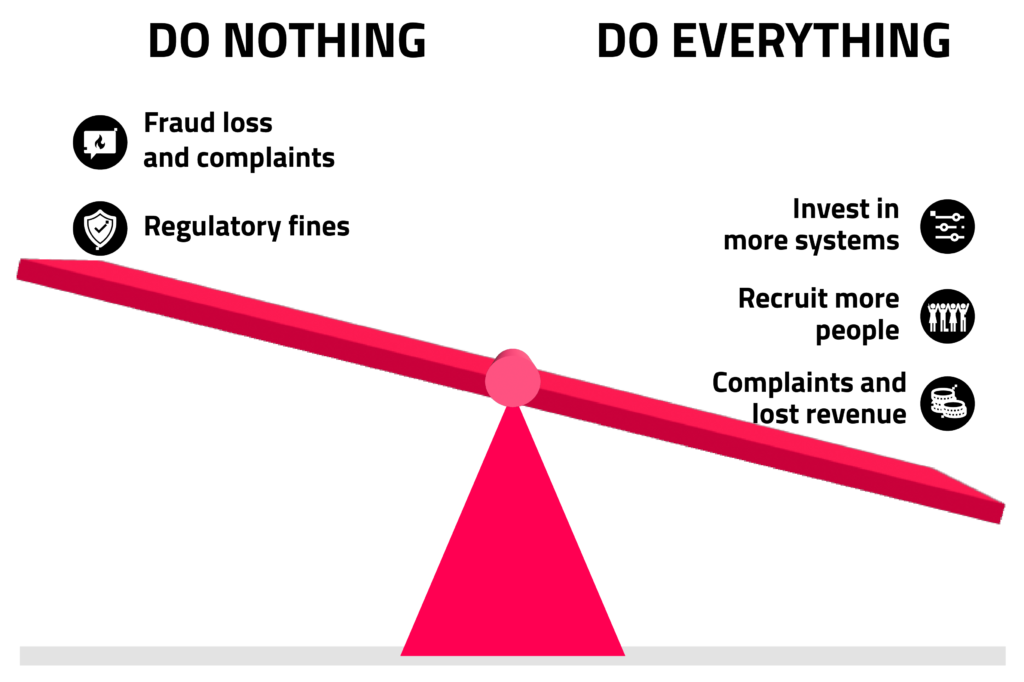

The Total Cost of Fraud is comprised of many different elements, some more direct, like refunding losses, and some more abstract like degradation in the customer relationship, such as those who stop using their card after a fraud decline. The costs are also a double-edged sword. On one edge there is the cost of ‘doing nothing’: claims from customers take effort to process and therefore have resource costs on top of the actual loss that needs to be refunded and then there are reputational damages that could reduce future revenue that would offset some of the costs; in this extreme of ‘doing nothing’ you would also have the potential for regulatory fines as you would be viewed as non-compliant and failing to protect your customers.

On the other edge”, ‘doing everything’ can be inefficient and negatively impact the customer experience. Of course, FIs must implement systems and strategies to prevent fraud. But overly complex, multi-solution approaches which layer technical debt and prioritise peripheral data sources such as behavioural biometrics will create a greater cost overhead- with the expectation of offsetting fraud loss costs – but in actuality these ‘spaghetti-systems’ can cause higher rates of false-positives: preventing customers from transacting, rather than not protecting them. And there could also be reputational damage and lost revenue even with increasing spend on systems if strategies are not optimised.

Cost Considerations and a Holistic View

Layers can offer a great combined solution that can react to varying fraud scenarios but can also have cost overheads. It can lead to systems that duplicate functionality or overlap and then are inefficient from a cost benefit point of view. Layered systems are often a result of legacy self-builds and point-solutions, rather than a holistic risk hub strategy.

Read: Buy vs Build in FinCrime Platforms

Calculating the Total Cost of Fraud means considering technology, services, and people. And finding the balance between technology and people costs may not be a simple answer. The balance is usually towards technology, but engineering and license costs can be high and will therefore need to prove they can produce a simplified and better-quality solution than a set of skilled people that may also expect high salaries.

Technology for Operational Efficiencies

Technology as an enabler for lower costs can come in different forms and have their own advantages and disadvantages.

- Cloud and Software as a Service (SaaS) approaches can be more predictable and transparent pricing than on premise deployments, but may mean relinquishing some control in relation to areas such as solution architecture to achieve this. The flexibility and scalability of modern cloud solutions supports dynamic scaling in line with business needs, to only pay for what you need or use rather than speculating for the future.

Read: How to overcome legacy technology constraints in financial services

- Artificial Intelligence is a wide-ranging area that could significantly reduce costs if the implementation fulfils the potential or expectation. An adaptable machine learning system that detects the level of risk for every event and then dictates the best action to take, would vastly improve efficiency through reduced false positives and reduced fraud. This could be taken further to optimize FTEs with bots communicating with customers and then making the final decision on whether to allow a transaction. Benefits could stretch further by the bots being able to adapt and automatically optimise decisions rather than needing specific processes and training to be planned in and rolled out. Offloading processes to AI would allow human to human interactions to focus on value-added services for the financial institution, such as complex fraud investigation or even outside fraud with the upsell and cross-sell of new financial products. And FTEs associated with the systems become more highly-skilled staff with clear career paths, that are easier to retain.

Fraud Operations and People Management to Reduce the Total Cost of Fraud

The key to getting the most accurate answer regarding the Total Cost of Fraud is to measure it and create a strategy to improve it, but just make sure that you don’t spend too much time and effort on it or ‘cost of fraud analysis and strategy’ will end up being its own cost line in the analysis!

As already mentioned, there are many points to consider, and the list can get very long. However, there will be a point of diminishing returns where the additional cost is so small it becomes irrelevant. For staff costs, you start with the people working alerts and writing rules. Then you add on people maintaining the systems they use. Don’t forget about the people managing and training those people. Recruitment and/or backfilling costs may need to be included as well. This will give you a broad total staff cost, assuming you know how many people you have and can add it all together.

System costs may be easier than staff costs, although can still be complicated. There is a decision to be made about initial set up costs. These can probably be excluded for an existing system but would need including for a new system if it is part of the change to reduce costs longer term. There will be infrastructure and software that needs to be maintained and upgraded with associated license and support fees and this is just to prevent any degradation of performance. For SaaS deployments, much of the cost will be clear and concise from the vendor. But for on premise deployments hardware and maintenance costs may be shared with other parts of the business, from centralised services.

Customer costs may be the easiest to calculate with the simple fraud value being refunded. The next level is more complicated but may not be significant if changes aren’t wholesale. The value the customer generates for the bank is based on their behaviour and may vary depending on if the customer is a fraud victim, a protected customer, or an incorrectly intervened upon customer. Complaints and ex-gratia payments could also be included but again, volumes and values are unlikely to be significant.

Modelling the Scenarios and Opportunities

The starting place for the next level of analysis could be to look to segment the activities so sections can be tackled in simpler chunks, such as customer interactions and system decisions, or onboarding and transacting. This might be a top-down view and can help you see where might have the best benefit potential. The challenge may still be that these segments are dependent on each other.

For example, when we look at customer interactions, we can look at how much the associated people and systems cost, but these may be the same systems that make the decisions and thus can’t be changed without impacting the decisions and related costs. You don’t want to introduce a system that halves the time to work a case but misses twice as much fraud and ends up not improving things. The key is having all the information laid out to assess this and then the scenarios can be worked through to see if making the system change does put you in an overall better position. One thing to remember is to map all the interconnecting variables and to factor in a forecast of how the fraudsters might react.

Coming back to the scenario of changing a system or a process to make it more efficient.: if we assume the change saves $100,000 in staff costs and would let through another $75,000 in fraud, then it could be assumed this is an improvement, but the increasing fraud could encourage fraudsters and the loss increases further and wipes out the benefit. This starts to look like a change with minimal or no benefit. What if the efficiency saving is reinvested in increased intervention and results in working more alerts for the same staff costs? This may stop more fraud and therefore deliver a cost reduction overall. There will be many similar scenarios to evaluate with big changes like replacing or rationalising systems for cheaper or more effective ones, and smaller improvements like streamlining or automating a process to need fewer people. The simplest and safest way to review these scenarios is to vary only one element at a time and then look to implement the scenarios with the largest improvement and highest confidence first. The cost of fraud analysis can then be used in an ongoing basis to track the benefits of changes being made.

Defining the Bottom Line

The end goal is to get the information you know onto one page and then work how it interacts and where you can add in more information, with a view to understanding the bottom-line impact on the business. Hopefully a spreadsheet can capture the information and the interactions and if it looks like you need a second tab, then you have probably gone too far and are into the realms of diminishing returns.

See how your Total Cost of Fraud sizes up against your peers with the Featurespace benchmark: The State of Fraud and Financial Crime

Share