Fighting Fraud: Breaking the Chain – the latest developments on the Fraud Act 2006

The Digital Fraud Committee was appointed by the House of Lords in the UK at the start of 2022, with a view to creating more positive action in line with the Fraud Act 2006. In November 2022, the committee published its report, Fighting Fraud: Breaking the Chain. The report outlined the enquiry by the committee into the scale of fraud in the UK, as well as a frank analysis of the failings of previous initiatives to the hold back the tidal wave of fraud sweeping the nation.

But the enquiry also offered some concrete actions that the UK private and public sectors need to take if we are to effectively act against fraud.

The Fraud Act 2006 and Digital Fraud Committee

“The Fraud Act 2006: An Act to make provision for, and in connection with, criminal liability for fraud and obtaining services dishonestly.”

In plain English, the Fraud Act of 2006 was about defining all the types of fraud (both within payments and outside of the financial ecosystem) and ensuring that fraudsters could be pursued by law enforcement. The reason it is back in the news now, is that in January of 2022 the House of Lords appointed a Digital Fraud Committee specifically to consider the Fraud Act 2006 in relation to Digital Fraud. This committee was re-appointed in May 2022 and has since published its report Fighting Fraud: Breaking the Chain.

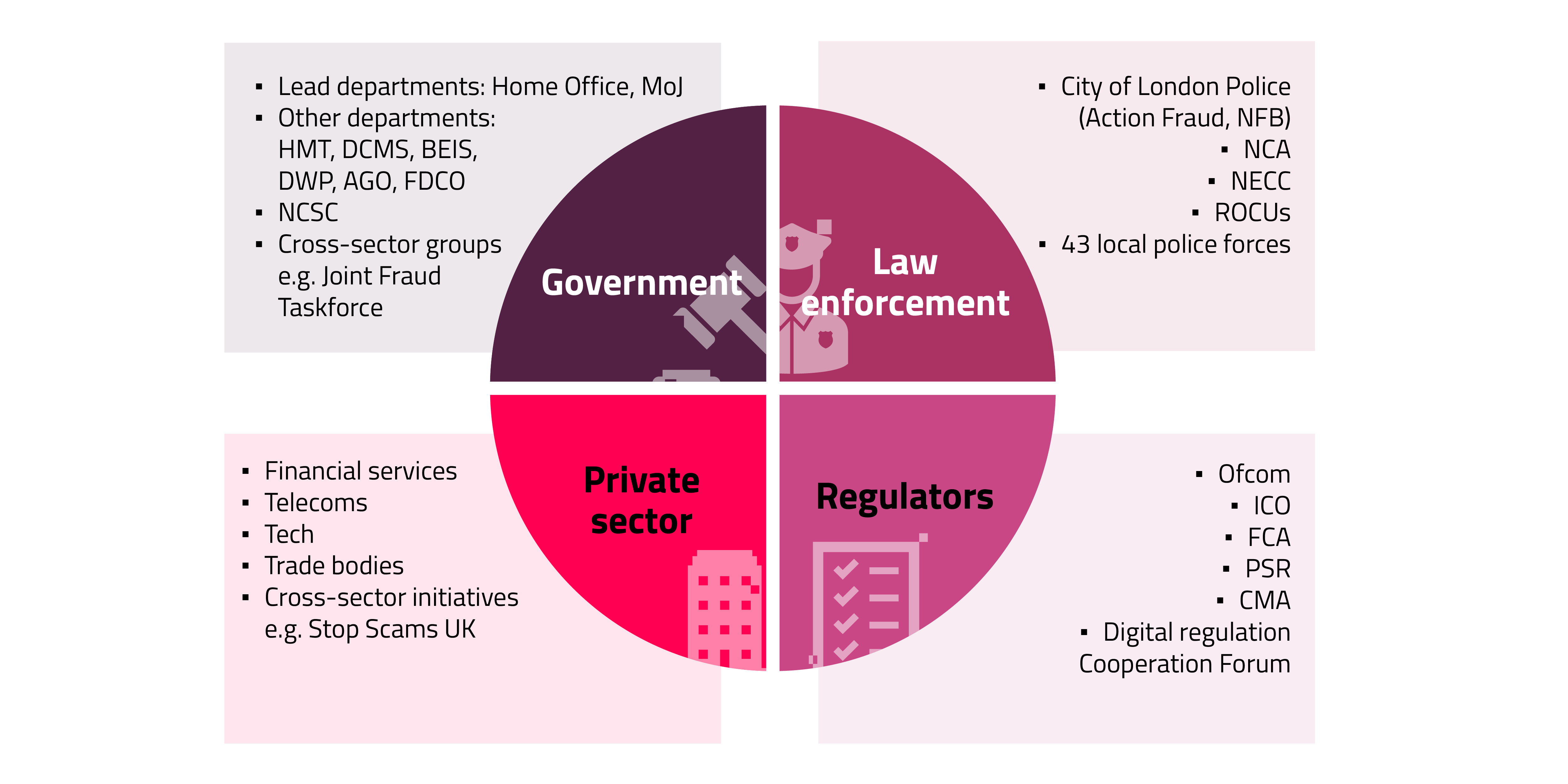

Within the details of the report is the full list of both government and public bodies that have a role in mitigating fraud, as well as some clarification on the role of private companies.

There are eight different government departments have a key role in mitigating fraud.

- The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) which has overall responsibility for the Fraud Act 2006.

- His Majesty’s Treasury (HMT)

- The Department for Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS)

- The Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)

- Attorney General’s Office (AGO)

- Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)

- The Department of Work and Pensions (DWP)

The publication of the report is a positive for the financial services industry, in that it formally recognises the size and scale of the challenge.

Fraud is the most commonly experienced crime in England and Wales, accounting for approximately 41% of all crime against individuals. This partly because of the historical ease of committing this crime – fraud can be conducted cheaply compared to other criminal enterprises – and the speed of return on investment for the criminals: fraud can be committed at pace. Lastly, with the historical disconnect between stakeholders hampering anti-fraud efforts, these crimes could be committed without fear of likely or successful prosecution.

“The state has retreated from the investigation and prosecution of fraud over the last 15 years.”

Mark Fenhalls, Chair of the Bar K.C.

Estimates suggest that despite the substantial growth in fraud, the decline in convictions could be as high as by two-thirds in 10 years. The report quotes former Treasury and Cabinet Office Minister Lord Agnew of Oulton, who goes as far as to suggest that the Government appears to suffer from a culture of complacency when it comes to getting a grip on fraud.

UK Challenges in fighting fraud

One of the biggest challenges highlighted by the report is the disconnect between key stakeholders, particularly internal government agencies. In the oral evidence given to the Digital Fraud Committee in March 2022, Lord Agnew went on to explain:

“ … there is painfully little join-up of departments to collaborate on issues that are complex, such as this. It applies on things like adult social care and homelessness. There are a whole range of interventions today that government needs to make to improve citizens’ lives, where it does not sit tidily in one department. Fraud is one of those examples.”

This is clearly evidenced in the fact that there exists a separate body for economic crime to digital fraud. The two bodies reduce their potential impact through a lack of transparency and infrequent meetings. The last set of publicly available minutes from the Economic Crime Strategic Board date from 2019.

Another disconnected stakeholder is law enforcement, which is both fragmented and underfunded when it comes to tackling fraud and financial crime. Task forces not working together in coordinated way and no clear outputs (minutes). Unfortunately reporting more accurately on growing fraud doesn’t lead to a reduction in crime. According to the report’s findings, only 1% of police and support staff are working on economic crime issues, which would explain the rising level of fraud. Criminal enterprises are running unchecked if their operations focus on fraud.

Percentage change in main crime types for the year ending June 2022 compared to year ending March 2020, England, and Wales

Perhaps the lack of funding and governmental focus stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of the impact of fraud on citizens. In February 2022, former BEIS Secretary and now former Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng commented that fraud was not a crime that people experience in their “day-to-day lives”. A startling and frankly incorrect statement.

According to the Government’s own Office for National Statistics, fraud is the crime that the highest number of UK adults reported experiencing between 2021 and 2022, with a 25% rise since the end of 2020. And data from UK Finance has consistently shown that fraud is increasingly targeting the UK population in their day-to-day lives, through scams.

“Social engineering, in which criminals groom and manipulate people into divulging personal or financial details or transferring money, continued to be the key driver of both unauthorised and authorised fraud losses in the first half of 2022.”

UK Finance, Half Year Fraud Report, H1 2022

Despite the changing nature of crime, it seems that policy and policing is not keeping pace.

Telco and Big Tech must act on fraud

It seems that the majority of focus for digital fraud prevention falls on financial services. And whilst banks and payments service providers (PSPs) should and could do more to prevent fraud and financial crime, there are other major players who also need to step up their anti-fraud interventions. Both Telco and Big Tech platforms are rife with digital fraud activity, but little is being done to stop the communications of fraudsters with victims.

“The telecom companies have some solutions, but they should do a lot more. So far, what they have done is the minimum and driven entirely by revenue.” Professor Feng Hao, Professor of Security Engineering at the University of Warwick

Before a fraudulent transaction can ever occur, the manipulation or deception of the victim happens through a communications channel. The report states that the current regulatory system does not impose sufficient leverage or incentives on digital platforms (such as social media networks or messaging apps) to combat fraudulent online messaging, particularly in comparison with the liability placed on the banking sector.

This liability is obvious in the current Payments Systems Regulator (PSR) consultation on Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud which looks to mandate the refund of scammed funds to victims by banks and PSPs. Telco and Big Tech bear no liability in this digital fraud. And neither are these non-banks regulated to leverage the data their hold on users for the protection of individuals.

“Tech firms and social media companies have huge power and resources but are regulated as if they did not. The financial services industry is heavily regulated by bodies with enormous power to enforce and penalise banks and rightly so. However, the largest social media firms and tech companies (who are some of the largest companies in the world) are regulated as if they have no power or responsibility to their users.” TSB

Industry action on fraud

It is clear that coordinated action on digital fraud is needed if the UK is to reverse the trends seen over recent years. The mapping of stakeholders shows the breadth of organisational collaboration needed to be effective in tackling fraud. And the report recommends converging some of these currently disparate initiatives.

Key stakeholders active in the response to fraud

It is hoped that converging will make working groups more impactful, and drive towards standardisation in efforts. This could include efforts such as defining fraud typologies that drive standardisation in reporting, and opening both working groups and regulation to encompass Telco and Big Tech.

The missing link in UK fraud prevention

Currently many of the report recommendations are highly theoretical, and it remains to be seen how they play out in reality. I remain doubtful as to their practicality, given a key misunderstanding of the nature of fraud within the report.

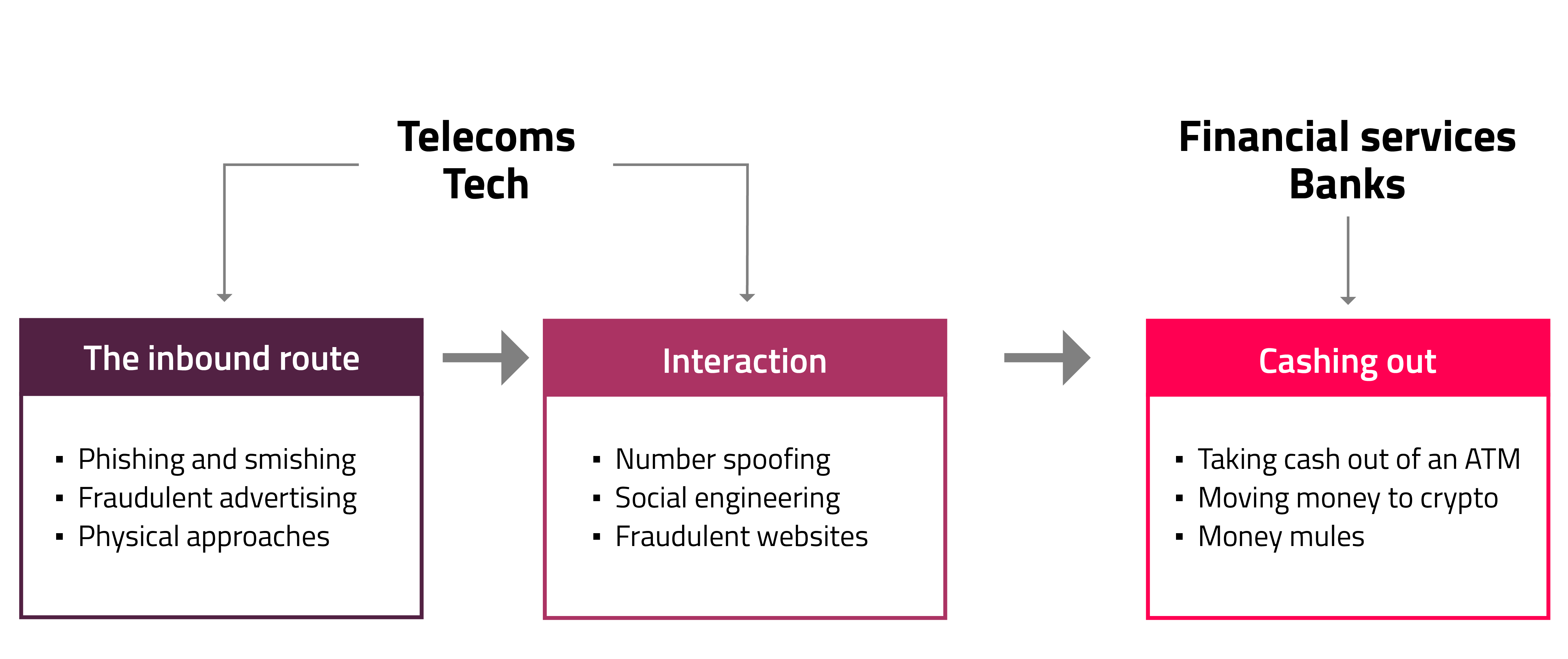

The report refers to fraud as chain, implying that it happens in a linear fashion. In a chain, if you remove one link the chain is ineffective, this is not the case for fraud as it is a web. This linear approach is why previous anti-fraud efforts have not worked and why a new approach is needed.

Removing a link in a web, the web still maintains its connections and strength. You can only take down a web by removing the key anchor points, and this is what fraud prevention needs to understand. All of the key stakeholders can target one of these points and destabilize the web until it is taken down. But like a spider’s web, it can be remade, and it will be. Criminal operations will not give up these current income sources a fight, and we need to be ready to outsmart them.

The Fraud Chain

The long arm of the law

Whilst all of the recommendations put forward in the Digital Fraud Committee report are a clear indication that fraud is being taken seriously, they remain just recommendations. The million-pound question is: how feasible are these steps, and will there be the much-needed infrastructure and financial backing to deliver them?

- Will new Police officers be recruited, or existing officers be retrained to focus on financial crime?

- Will legislation be put in place to ensure that Telco and Big Tech companies are held responsible too?

- Will financial crime awareness in government be raised to the level that is needed?

Fraud is a crime that transcends borders, and the organised criminal gangs that perpetrate it span across continents. Whilst the UK recommendations are necessary, we need to think globally. We have a responsibility to set an example to the rest of the world – not only as a major economic player, but as a hub for financial crime prevention and detection. When you build a strategy to prevent one type of financial crime you drive the criminals to another method, in the same way action on fraud in one country will push crime over the border to another. We need to think bigger.

Collaboration is the key, not just with internal governmental bodies, but international governments, law enforcement, regulators, banks, and the private sector. Social media companies have a reach that cannot be matched, and an important role and responsibility in halting the use of their platforms by bad actors.

Organised criminal gangs are well-funded, well-organised entities that often eclipse their legitimate diametric agencies in terms of resource and headcount. They have HR teams, marketing teams… everything a legitimate business has. And there needs to be an appropriate level of investment in legitimate organisations to counter criminal enterprises. From a UK perspective, unfortunately we are not yet seeing stakeholders put their money where their mouth is.

Counter-fraud collaboration

Criminals aren’t bound by regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and their flow of data is unheeded across multiple platforms that are no longer just the purview of the dark web: social media platforms such as Telegram host thousands of channels dedicated to sharing, selling, and promoting financial crime techniques without fear of reprisals.

Where is the platform for fraud fighters to share techniques and methods to prevent these attacks? There are some organisations that are making important headway, such as the Merchant Risk Council (MRC) which operates multiple forums inviting representatives from merchants, as well as issuing and acquiring banks, to discuss openly (or anonymously) trends they are seeing. Members share insights on how they are tackling new fraud typologies. MRC also operates a Slack channel for its members to communicate in real-time (as fast as the criminals share information), offering a community without prejudice or competition, but rather a global consortium with a common goal.

Banks and PSPs can securely and legally share data. P27 in the Nordics is a great example of how banks in direct competition with each other can collaborate and break down historical siloes for the benefit of all. Will it happen overnight? Unfortunately, the answer is no, but P27 is setting an example with a step in the right direction, evidencing a willingness and openness to throw off the constraints of past approaches that don’t fit the modern, digital payments ecosystem. There are lot of hurdles we needed to clear, but when there is a clear and common goal, we are stronger together than we are apart.

It’s clear that more coordinated action is needed to tackle fraud, which is increasingly becoming a national crisis in the UK. Part of that coordinated action is better understanding the gap between fraud prevention in the private sector, and crime prevention in law enforcement.

My colleague, Todd Raque, ex-cop turned AML expert, recently wrote about how to overcome data fragmentation and integrity. His insights show us how we can begin to close the gap.

Read more >> Why it’s time to think like a cop to prevent cryptocrime

Share

by

by